4-bit random numbers

While I accept that a toy 4-bit microprocessor probably isn’t a subject that warrant multiple posts, I’m unable to resist. Apologies.

After playing with my GMC-4 for a couple of days, the initial novelty of hand assembling programs had well and truly worn off, so I turned to the assembler and simulator available on the web. After a couple of minutes of use though, it was obvious that a simulator wasn’t at all what I wanted.

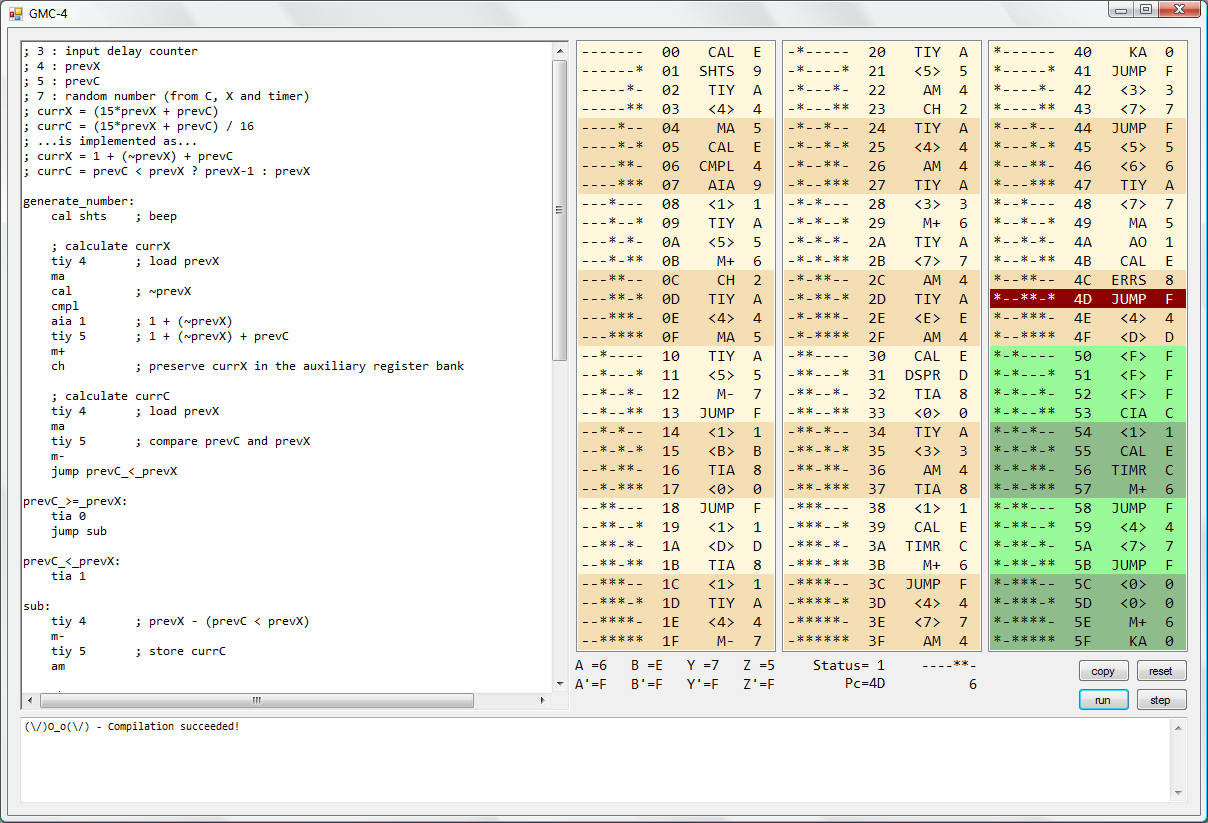

After all, if I wanted to type in a program nibble by nibble, I may as well do it on the hardware itself. What I really wanted was an integrated assembler and debugger. Luckily, the instruction set is very basic, so it didn’t take very long to put one together:

The left pane is the source window. The three columns on the right show the contents of memory; program memory is shown in Wheat & Cornsilk, data memory in DarkSeaGreen & PaleGreen, the current instruction is highlighted in DarkRed. The colouring is intended to make it easier to follow through the code when typing in the machine code on the hardware.

The jumble of text below the memory view shows the state of the eight registers, the status flag (see my previous post), program counter, seven-segment display and binary LEDs. There are buttons for copying the contents of memory to the clipboard, running the program, single-stepping and finally simultaneously compiling the source and resetting the state of the machine. The bottom panel shows any exceptions that might get thrown by the assembler or emulator (I didn’t bother to spend much time on error handling).

The reason op-codes are still shown for data memory is that (aside from addressable ranges) the GMC-4 makes no distinction between code and data memory. The neat thing about this is that the hardware has no problems executing code that lives in data memory; it also doesn’t mind if those instructions get modified during program execution, which means… self-modifying code! I’ve not found a way to make reasonable use of this, but it’s kind of cool nevertheless.

In the unlikely event that anyone’s interested, I’ve shoved the code up on Google. It’s written in Good Ol’ WinForms, as my fleeting love affair with WPF ended once I decided that I’d rather be productive than fashionable.

For one of the “games” I wrote, I needed a random number generator. Unfortunately, with 4-bit addition and subtraction my only available mathematical operations, it wasn’t immediately obvious how to go about it.

A bit of searching around led inevitably to Wikipedia and multiply-with-carry random number generators. I went with lag-1 MWC for simplicity, which is defined as:

\(x_n = (ax_{n-1}+c_{n-1})\,mod\,b\) \(c_n = \lfloor\frac{ax_{n-1}+c_{n-1}}{b}\rfloor\)

Being limited to 4-bit numbers, a natural choice for b was 16 and a quick exhaustive search for a showed that a value of 15 yielded the sequence with the longest period (around 120) and distribution of numbers that wasn’t wholly intolerable (it at least covered all the digits). As an added bonus, using these values for a and b meant that the multiplications and divisions could be done away with completely:

\[x_n = (15x_{n-1}+c_{n-1})\,mod\,16 \\ x_n = 1 + \tilde{x}_{n-1} + c_{n-1}\] \[c_n = \lfloor\frac{15x_{n-1}+c_{n-1}}{16}\rfloor \\ c_n = \begin{cases} x_{n-1}-1, & c_{n-1} < x_{n-1} \\ x_{n-1}, & otherwise \end{cases}\]That crappy little tilde above the x is meant to represent a bitwise not - my LaTeX is pretty weak I’m afraid.

4-bit random number generation is not exactly a widely discussed topic on the internet, so I don’t know if there’s a better method. This worked well enough for my purposes though. Quality wise, it’s probably on par with RANDU.